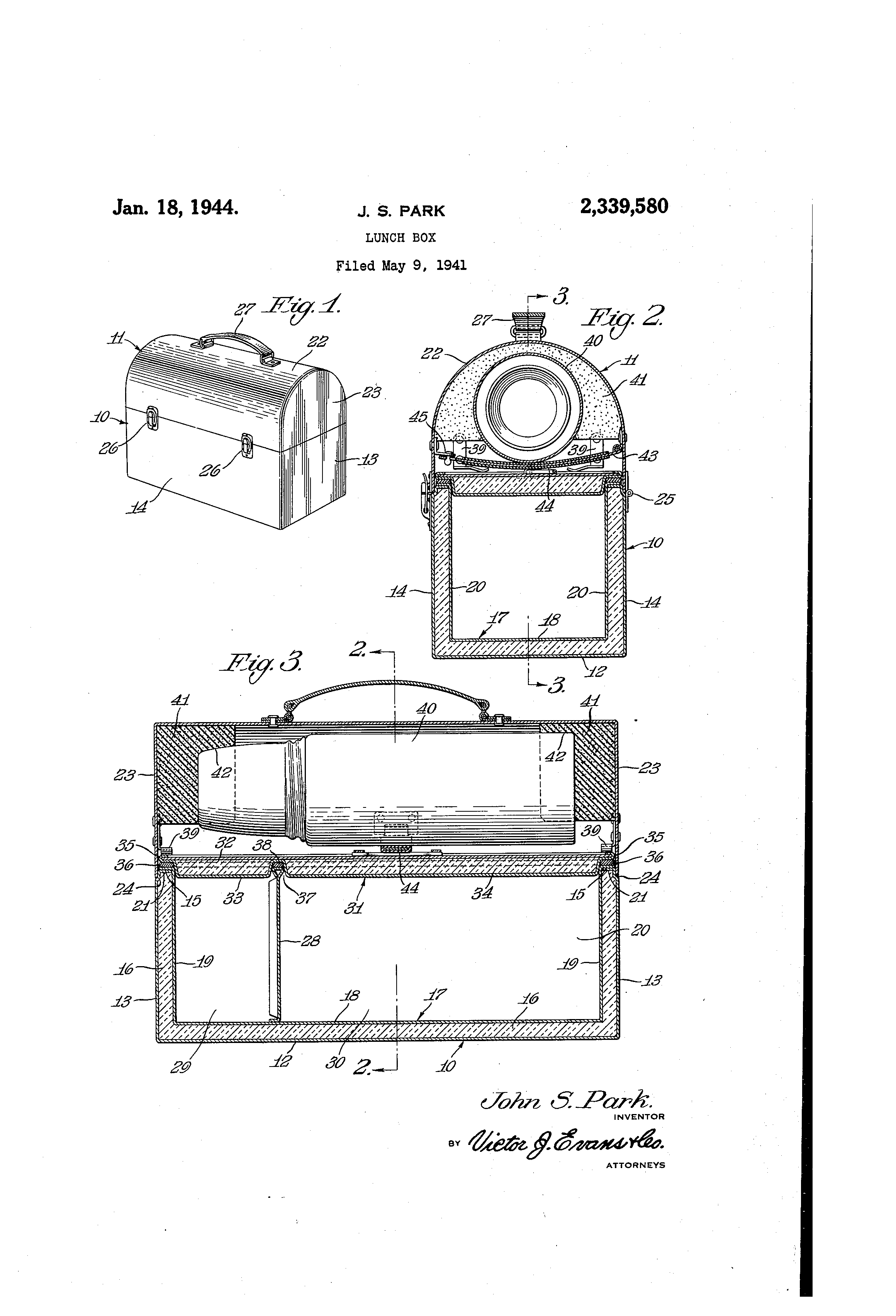

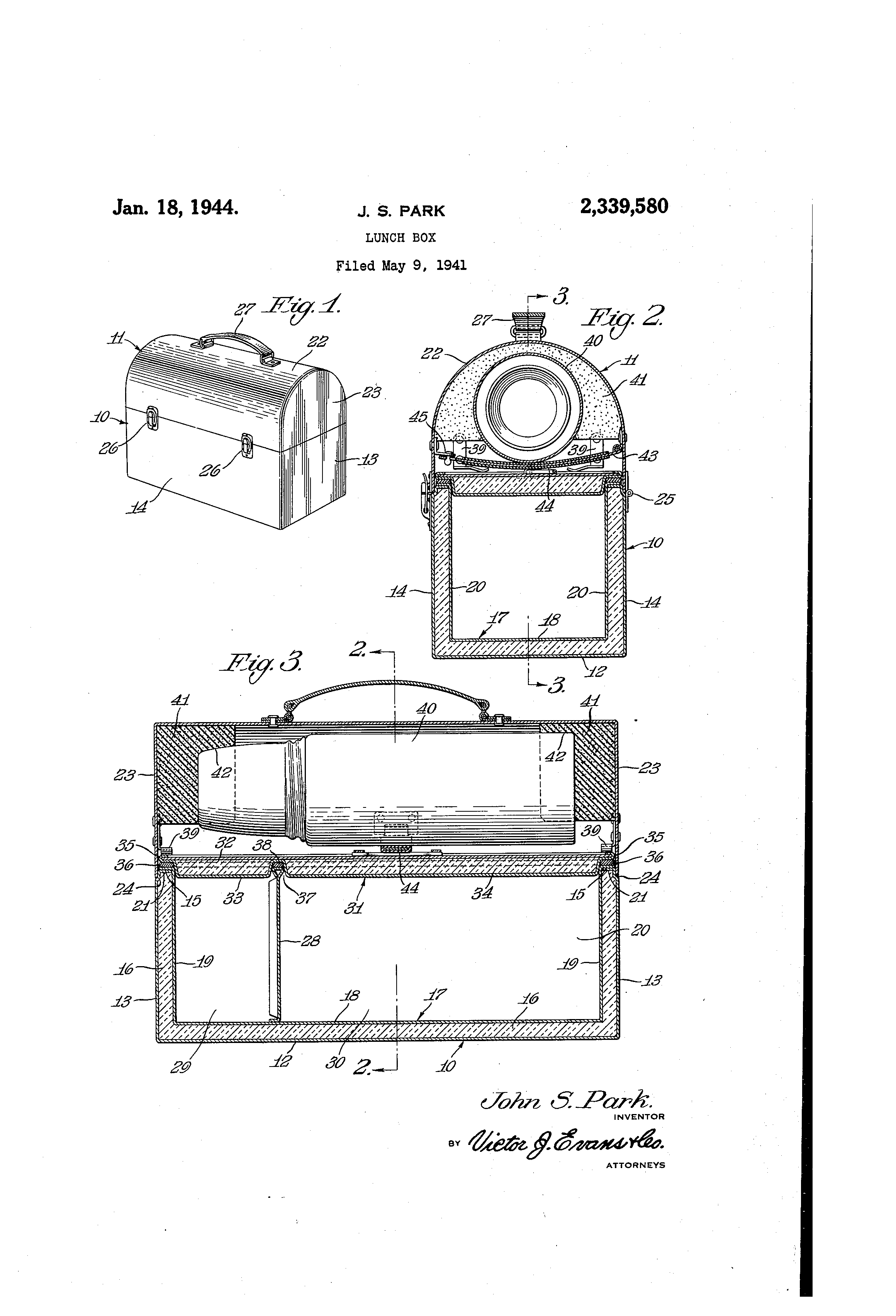

Black or silver, it was shaped like a camel back trunk, with two chrome latches on the front. A swing arm locked the glass-lined thermos inside the domed lid. The metal “workingman’s” lunchbox—although plenty of women carried one, too—symbolized the can-do spirit of manual labor.

My dad carried a black metal lunchbox to a General Motors factory., where he worked the night shift as a machinist. Each weekday afternoon at around 3:30, my mother would lovingly stuff his lunchbox with enough food to feed the Donner Party: five sandwiches on white bread—two grape jelly, plus one each of bologna, pickle-pimento loaf and peanut butter—plus an apple and a thermos of whole milk.

The work was such that my father did not get fat. At 5 feet 10 inches and 185 pounds, he had forearms the size of rear axles, sculpted by years

of wrestling with borers and grinders, jig mills and lathes. He would stand all night at his workbench, his feet snug and sweating in leather boots that deflected sharp flakes of hot steel onto the oily concrete floor.

Meanwhile, in the cool cave of his lunchbox slept the sandwiches, which, like his toes, needed protecting.

In 1979, nearly 20 million men and women were working in factories and mills. A sturdy metal lunchbox could withstand the rigors of the harsh environments—heat, cold, falls from tables and benches.

Yet as the number of blue-collar workers declined so did the need for the metal lunchbox. My dad got a promotion and began wearing a tie and regular shoes to work. He carried his lunch in a plain brown sack.

Now we work at service or desk jobs. To bring a metal lunchbox into a such a workplace would be pretentious. What would we protect our lunch from? [2:00]

Falling megabytes? Paper cuts? Office gossip?

In the daily ritual of lunch making, my mother’s final touch was to write my father a note and then slip it among the sandwiches. I don’t know the contents of these letters—to read them would have been an unthinkable breach of my parents’ intimacy—but I always knew when she had finished one by the brisk strokes of her pen as she dashed a constellation of x’s and o’s at the bottom of the page.

My father took his lunch break at 8:30 each evening. I imagine him sitting at his workbench with his lunchbox agape and reading a love letter from his wife, who at that moment was readying their children for bed. Then he would neatly fold it and place it inside for safekeeping.