I Walk the Line: Protecting affordability near Buchanan Boulevard

Story and photos by Lisa Sorg

Note: The public comment period on the Draft Environmental Impact Statement ends Oct. 13. You can comment via www.ourtransitfuture.com .

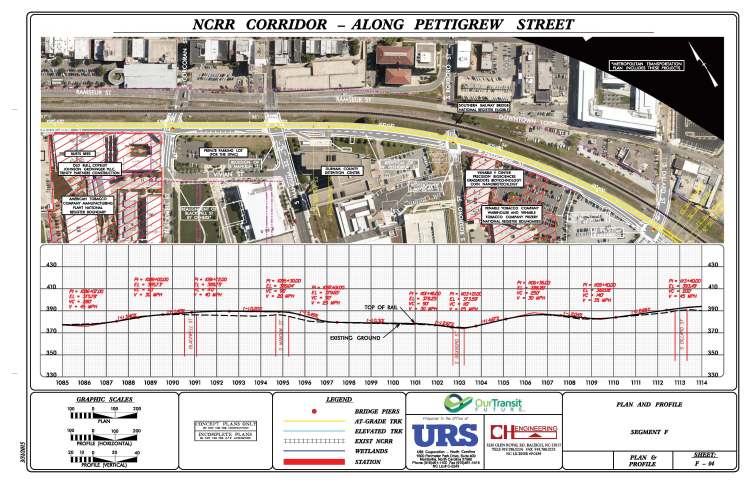

Near Brightleaf Square, an eerie stretch of West Pettigrew Street parallels an active rail line. Part of the “street” is gravel, and more closely resembles a cowpath. It then crosses Gregson, and curves past the remains of an old, brick house, its lot strewn with trash. Beneath some leaves, I find a woman’s bracelet.

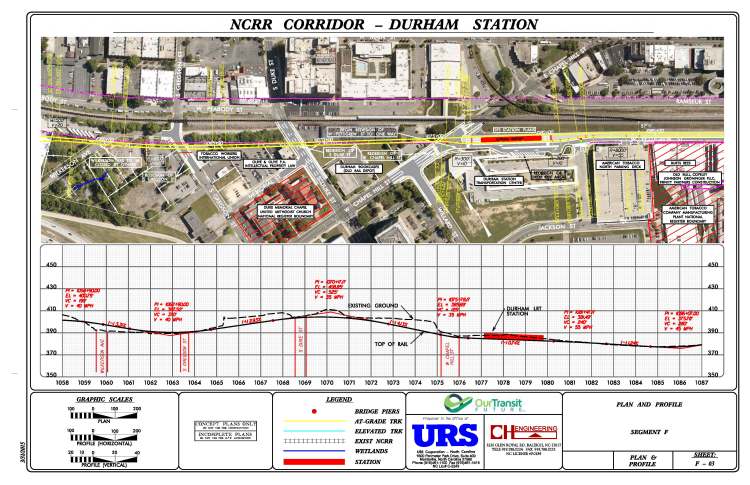

Pettigrew Street dead-ends at the Duke University transportation center and impound lot, site of the future Buchanan Boulevard station. For now, though, buses await their scheduled maintenance, garbage trucks nap between routes and discarded parking lot booths transform into terrariums as vines climb inside them. Cars, having violated Duke’s strict parking rules, have been jailed until their owners bail them out.

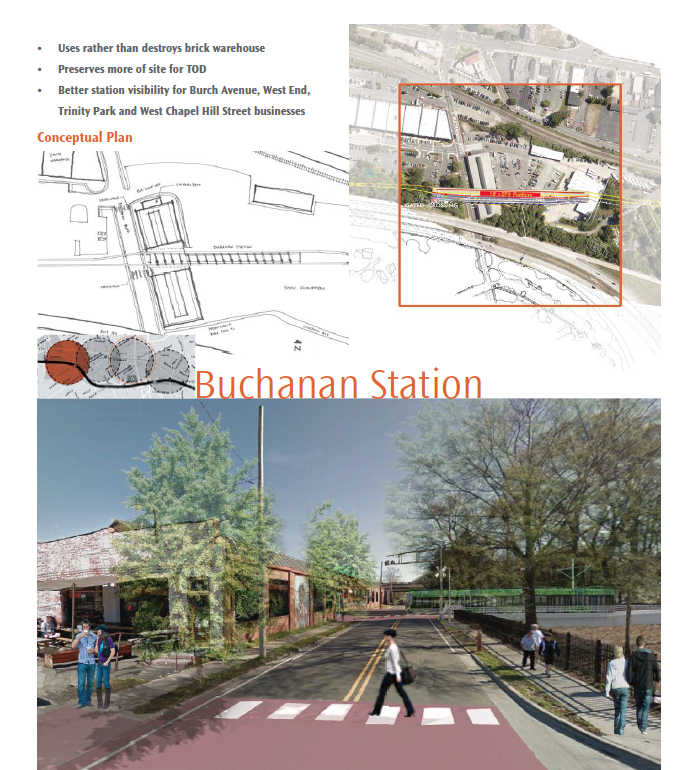

The line originally was to run near Smith Warehouse, but considering the building’s historic significance, the railway was deemed too close. So now, it runs a tad south, through the Maxwell Street parking lot, parallel to the Durham Freeway. As planned, the station would be couched off the street, and take out an old, brick warehouse, emblazoned with a mural of Pauli Murray, the Episcopal saint and civil rights activist.

But Durham Area Designers, a volunteer group of urban planners and architects who’ve scrutinized the proposed plan, believe the warehouse can be saved and reused. They submitted public comment, complete with drawings, showing a different proposal that not only preserves the building but also provides more space for transit-oriented development and better connections with the neighborhoods.

150930_DAD_Durham-Orange Light Rail Transit Project

These neighborhoods—in particular, West End and Burch Avenue, and less so, the already tony Trinity Park, which borders Duke East Campus—are vulnerable to the effects of gentrification: Displacement of low- to moderate-income residents and local businesses along West Chapel Hill Street that have stuck by this neighborhood through thick and thin.

“We’re seeing changes in neighborhoods now. Now is when the planning is happening. Now is when decisions are being made.” —Selina Mack, director of Durham Community Land Trustees, a nonprofit that preserves and creates affordable housing

At Durham CAN meetings, residents have been focused on how to preserve affordable housing around station areas, including the West End and Burch Avenue. Affordability is very much at risk. Mel Norton of the Durham People’s Alliance analyzed 10 years’ of sales data in these neighborhoods, which shows home prices have increased more than 100 percent.

“There will be a significant increase in rents and property values. It’s happened nationwide. We want the benefits of light rail but not the displacement.” —Patrick Young of the Durham City-County Planning Department

As for renters, a UNC study released this year (see page 36 at the link below for this particular neighborhood), indicated that 78 percent of dwelling units within a half-mile of the station are rentals. Forty-five percent of dwelling units are considered to be affordable; however, very few are subsidized, meaning that increases in property values could compel private landlords to increase rents beyond their tenants’ reach—or flip the houses altogether. The study is here: affordablehousing_possiblesites

This is one of the most diverse neighborhoods in the city, home to the annual Our Lady of Guadalupe parade, Immaculate Conception Catholic Church, the Islamic Center and Joy of Tabernacle storefront church. It sustains the Durham Co-op and the Taiba Middle Eastern Grocery. It’s certainly worth protecting.

Census figures for Burch Avenue neighborhood, from the Durham Neighborhood Compass

Total population 584

Latino 12%

White 51%

Black 31%

Youth under 18 13%

Median household income $24,943

Percentage of residents who are renters 83%

Percentage of renters who spend more than 30 percent of income on house 64%